Measuring user agency in novel modalities using expectation priming

In Exploring game interaction using brain-computer interfaces, I noted that additional research to explore is how the perceived reliability of a system could impact the mainstream adoption of new techologies like brain-computer interfaces. I find this to be an important topic to explore because incorporating new and assistive tech into mainstream use cases, like gaming, can help make these tools cheaper and more widely accessible.

I update the UX Research Directory with the Wizard of Oz testing method, and used BCI as an example test scenario…so I thought I’d write out a short research proposal on the topic. Maybe someday, I’ll have the means to explore this concept.

First, let me set a baseline of what I know…

Existing research

Perceived control / user agency

In human-computer interaction, perceived control refers to a user’s sense of agency or feeling in charge of the technology. Users strongly want the feeling that their actions directly influence the system’s response [1]. Interfaces should respond predictably to user input and avoid unexpected actions, so users feel they are steering the interaction rather than the system taking over. This is a widely known interface design heuristic. If users feel in control, even within the constraints of the system, they tend to be more confident and engaged, regardless of how much control they actually have [2].

Error tolerance

Error tolerance describes how much fault a user is willing to accept from a system before losing confidence or abandoning it. It plays a pivotal role in technology adoption. If users encounter too many errors early on, they may decide the product is unreliable, but if errors are infrequent, minor, or easily fixed, users may be more forgiving and continue using the technology. A key factor is whether the system design helps users recover from errors gracefully. Usability research shows that users (even experts) will make mistakes, so interfaces should account for that.

Whose error is it anyway?

I’ve observed many people using systems throughout my career, and I’ve yet to find a distinct pattern for how and how “blame” is passed on to a system, with the exception of one scenario: the system is new. How users attribute an error can dramatically shape their experience. Anyone who’s ran a usability test has likely experienced one or both scenarios:

- The user self depracates, questioning their abilities, when in reality, the issue is caused by a bad design decision (this is easy to remedy in studies, but much harder to correct in the real world, as these users are likely to abandon the system altogether)

- The user slips or makes an error, but shifts fault on the system (this is harder to course-correct in a controlled study, but easier to fix with more advanced users by reinforcing system updates)

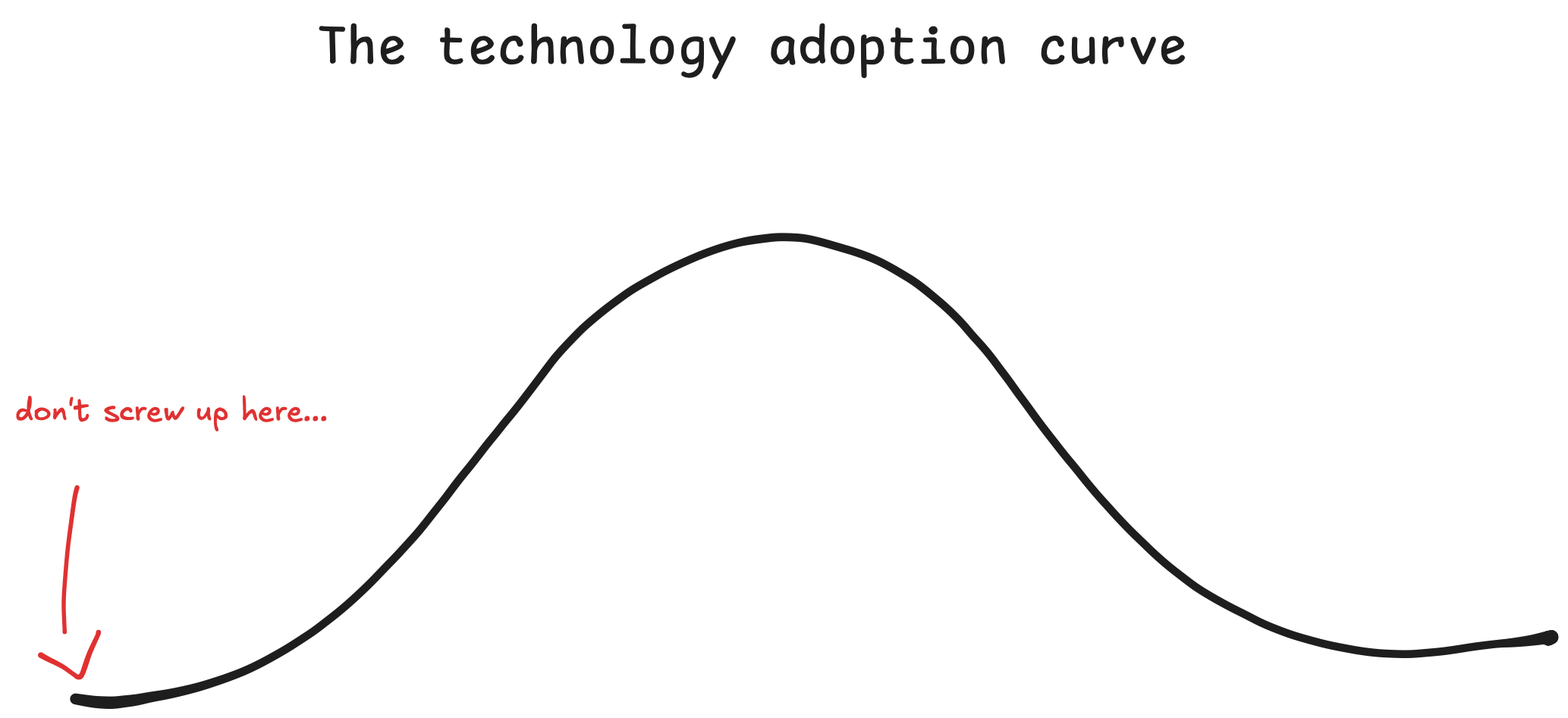

Misattribution is harmful. Users blaming themselves may frustrated with technology in general, whereas users blaming the system may abandon it outright. As you can see by my very sophisticated graphic, you have to get past the early adopter phase of the adoption curve for a new system or product to take off.

I’ll probably write more about error handling in another note…Now on to the study idea.

Study idea

This study would look at how expectations shape user agency and perception of errors in brain-computer interface (BCI) gaming. Using the Wizard of Oz method, where a researcher manually controls system responses behind the scenes, the goal is to understand how players attribute system errors based on how reliable they think the system is.

Study Design

Two groups of participants experience the same BCI-controlled game but with different expectation priming.

- Group A is told “This technology is cutting-edge but still experimental, and accuracy is unpredictable.”

- Group B is told “This system has been rigorously tested and achieves 98% accuracy.”

Both groups experience the same controlled error rate, manually introduced. The focus is on how they interpret failure:

- Do those expecting uncertainty adapt more easily?

- Do those primed with high reliability become frustrated, blaming the system or their own actions?

Potential Insights

- How expectation setting influences user trust

- How users attribute failure

- Whether belief in system reliability affects perceived performance

- Whether users adjust their strategies differently based on expectations of failure versus assumptions of near-perfect accuracy

Why the Wizard of Oz Method?

This method ensures each participant experiences identical conditions without the inconsistencies of real BCI signal processing. It allows for a controlled way to test perception and behavior without technological limitations skewing results.

Ethical Considerations

Participants should give informed consent, even if full details on expectation priming are only revealed after the study. A debrief should explain how the system was controlled and how perception influenced their experience. Frustration is a relevant factor, but users should not feel manipulated or discouraged.

Broader Applications

Findings from this study could inform not only BCI gaming but also AI-driven UX, adaptive difficulty in games, and human-technology interaction models. It could also serve as a basis for understanding how to define minimally viable products to garner adoption.

Supporting research

-

H. Limerick, D. Coyle, and J. W. Moore, “The experience of agency in human-computer interactions: a review,” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, vol. 8, Aug. 2014, doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00643.

-

J. Zhang, Y. Luximon, and Y. Song, “The Role of Consumers’ Perceived Security, Perceived Control, Interface Design Features, and Conscientiousness in Continuous Use of Mobile Payment Services,” Sustainability, vol. 11, no. 23, p. 6843, Dec. 2019, Available: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/11/23/6843/htm